Rebecca Kennison, Judy Ruttenberg, Yasmeen Shorish, and Liz Thompson

This white paper and all supporting materials have been archived on LISSA (LIS Scholarly Archives). Supporting materials include data analysis and redacted transcripts of the focus groups.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services LG-73-18-0226-18. The views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this white paper do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The National Forum described here was proposed as a first step in surfacing community requirements and principles toward a collective OA collection development system (Shorish et al. 2018). The Forum asked participants to envision a collective funding environment for libraries to contribute provisioning or sustaining funds to OA content providers. A critical component of this project was to bring together groups of interested and invested individuals with different priorities and perspectives and begin to build a community of engagement and dialogue. By analyzing focus group feedback and leveraging the insights and interactions of participants, this paper presents the challenges, opportunities, and potential next steps for building an OA collection development model and culture based on a community of collective action.

The focus group feedback and our own research into the field surfaced these key observations:

- The open content landscape is massive and unwieldy. Librarians at large universities, even those with dedicated scholarly communication librarians, were as likely to cite being overwhelmed and under-informed as were those from smaller staffed institutions.

- There is a strong desire for clear criteria and a centralized clearinghouse or catalog of trusted projects, products, and platforms that could be used to aid decision-making and to speed the approval process.

- Paying for OA content creation (e.g., open educational resources [OER], article-processing charges [APCs], or subventions) was often conflated with supporting OA content consumption (e.g., arXiv, Knowledge Unlatched collections, Open Library of the Humanities). The former was most often seen as a locally beneficial activity and the latter as part of collective service.

- Supporting OA content is considered by almost everyone as a supplemental “nice to have,” rather than as core to the collection — and it is being funded that way.

- One particular type of open content — OER, especially textbooks—has widespread support across all institutional types and sizes, and successful adoption of OER could be leveraged as an entrée into developing support for other types of open content.

- Collective funding challenges are shared across a variety of institutions. Regardless of institution type, libraries face similar challenges in terms of making locally compelling arguments for supporting collective funding for open content.

- Transparency is important to the community of OA investors, including pricing, values, governance, and preservation.

In a world transitioning to more open, networked scholarship, this white paper provides insights into the community’s thinking, the language library workers use to discuss collections, and the perceived constraints and barriers to participation that need to be further researched, understood, and addressed to set up a successful collective funding environment.

INTRODUCTION

Academic collection development and acquisitions librarians use subscription agents, book aggregators, and approval plans to maximize efficiency by reducing the number of relationships and transactions necessary to purchase and license collections. Library consortia leverage these networks and tools to make smart, collaborative collections decisions aligned with local and regional priorities, resource-sharing relationships, and shared print agreements. For open access (OA) content, however, particularly from new content creators, there are limited tools and mostly only informal arrangements.

The National Forum described here was proposed as a first step in surfacing community requirements and principles toward a collective OA collection development system (Shorish et al. 2018). The Forum asked participants to envision a collective funding environment for libraries to contribute provisioning or sustaining funds to OA content providers. Through a series of successive focus groups, a non-random but diverse sample of academic librarians was asked about the conditions under which they would participate in funding OA content.

A critical component of this project was to bring together groups of interested and invested individuals with different priorities and perspectives and begin to build a community of engagement and dialogue. By analyzing focus group feedback and leveraging the insights and interactions of participants, this paper presents the challenges, opportunities, and potential next steps for building an OA collection development model and culture based on a community of collective action.

A criticism occasionally levied at OA development work is that it is either purely theoretical — relying on arguments of altruism and the public good to produce change — or results in “solutions” that are hastily implemented by OA advocates in ways that either do not scale to other institutions or do not consider how the changes affect existing collection development practices and culture. Our focus group forums were designed as foundational conversations, to serve as a bridge between the theoretical and the specialized solution. Before the academic library profession can consider how to encourage a culture of collective action and community building, we must understand the barriers to and concerns about such a cultural shift. The Forum was an information-gathering activity to build a shared agenda for meaningful research and development. While future research questions and developments are out of scope for this project, we hope that the conversations within the focus groups and that this white paper will inform other efforts and help motivate participants and readers to continue the work.

Recent Developments in Collective Funding Frameworks

Over the past two years, several large-scale, ambitious initiatives have launched to provide collective funding of open scholarly infrastructure. These initiatives aim to aggregate fundraising and/or payments, along with collectively vetted recommendations for what pieces of the scholarly infrastructure are either most in need of support or most critical to scholarship. By and large, these new initiatives were not on the radar of focus group participants since many are still at the formation stage.

Many of these new initiatives operate through a lens of collective action. “Collective action” refers to cooperative work across a group of entities to achieve a common goal. However, collective action comes with its own challenges, often termed the “collective action problem” (Wenzler 2017). The collective action problem refers to the disincentives to participate collectively, such as local priorities, unequal monetary contributions, or compromised goal-setting (Dowding 2013). Collective funding for open scholarly infrastructure is a dynamic area in libraries, and several projects have merged since they were independently formed. While our “OA in the Open” project initially envisioned a distinction between open content and open infrastructure, we recognize that the boundary is increasingly porous, as focus group participants themselves pointed out. The following initiatives will likely have implications in any further work developed from this project.

The Global Sustainability Coalition for Open Science Services (SCOSS)

Formed in 2017, the mission of SCOSS is to identify non-commercial services essential to open science, to make recommendations on which services should be considered for support, and to work with those services to set fundraising targets. Potential funding recipients apply to SCOSS for consideration, and the SCOSS Board and Advisory Group evaluate the services based on criteria including “value to communities such as funders, universities, libraries, authors, research managers and repositories; and on details pertaining to their governance structure, costs, sustainability measures, and future plans.” The goal is to set a three-year funding target so that “research affiliated organisations and institutions of all sizes and funders throughout the world” contribute to the service until they become more self-sustaining.

The SCOSS funding structure is based on recommended contributions from large organizations from high-income countries, small organizations from high-income countries, funders, governments, organizations from low- and middle-income countries, and consortia of ten organizations or more. SCOSS itself is funded through a one-time service fee, charged to the entity receiving collective funds.

SCOSS is governed by a Board composed of representatives from member organizations. The SCOSS Board is the decision-making body, and it is advised by the SCOSS Advisory Group, which evaluates funding proposals and maintains a list of strategic areas in OA and open science.

Invest in Open Infrastructure (IOI)

From its launch in May 2019, IOI has been a coalition of organizations and other adjacent projects, some of which (like SCOSS) are continuing independently even as they participate in IOI. IOI is motivated by three core contentions: (1) open infrastructure is better aligned with and responsive to scholarship than proprietary systems, which capture and control the scholarly process and data; (2) pieces of open scholarly infrastructure are not interoperable with each other and lack coordination with the community, which makes them vulnerable financially; and (3) financial vulnerability and lack of resources makes open infrastructure susceptible to for-profit acquisition.

To address these related challenges, the IOI coalition proposes a two-part strategy: (1) a framework for recommending pieces of the open scholarly infrastructure, including criteria, tracking mechanisms, collaboration among services, advocacy and engagement, and a method for identifying resource needs; and (2) a fund to pool money from institutions and agencies to act on the framework’s recommendations.

IOI is governed by a steering committee representing its participating organizations, including SPARC, SPARC Europe, OPERAS (Open Scholarly Communication in the European Research Area for Social Sciences and Humanities), the Joint Roadmap for Open Science Tools (JROST), the Open Research Funders Group (ORFG), and Towards a Scholarly Commons.

Near-term activities for IOI include implementing a governance model and developing the IOI funding model and strategy.

Mapping the Scholarly Communication Infrastructure

The OA in the Open project team has been in communication with David Lewis and Mike Roy since the planning of this Forum. With funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, in June 2019 Lewis, Roy, and Katherine Skinner of the Educopia Institute produced “Mapping the Scholarly Communications Landscape: 2019 Census” and will conduct a survey of library investments in scholarly communication services later this year.

The 2019 Census was devised using the Educopia Institute’s Community Cultivation Field Guide as a framework. As such, it concentrates on a key weakness in the scholarly communication landscape, which is a lack of funding for service outreach and fundraising — precisely the problem IOI is trying to solve through a framework and a fund.

OA Switchboard

The OA Switchboard, which eventually will be located at http://www.oaswitchboard.org/, is being organized by the Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association (OASPA) and is currently in its design phase. The Switchboard is “designed to enable publishers, academic institutions, and research funders to seamlessly communicate information about open access publications.” It does so not through a central payment system or an intermediary, but rather by an exchange of metadata. The OA Switchboard is envisioned as infrastructure to minimize the one-to-many transaction burden that characterizes the landscape libraries are currently facing, but avoids the legal and contractual challenges of collecting funds centrally. However, “participating publishers would also be able to send a Payment Request via the OA Switchboard … [which] would enable funders and institutions to automate the oversight, management, and reporting of the agreements that they have entered into, even if no individual payment is being made as a result of a specific publication.”

METHODS

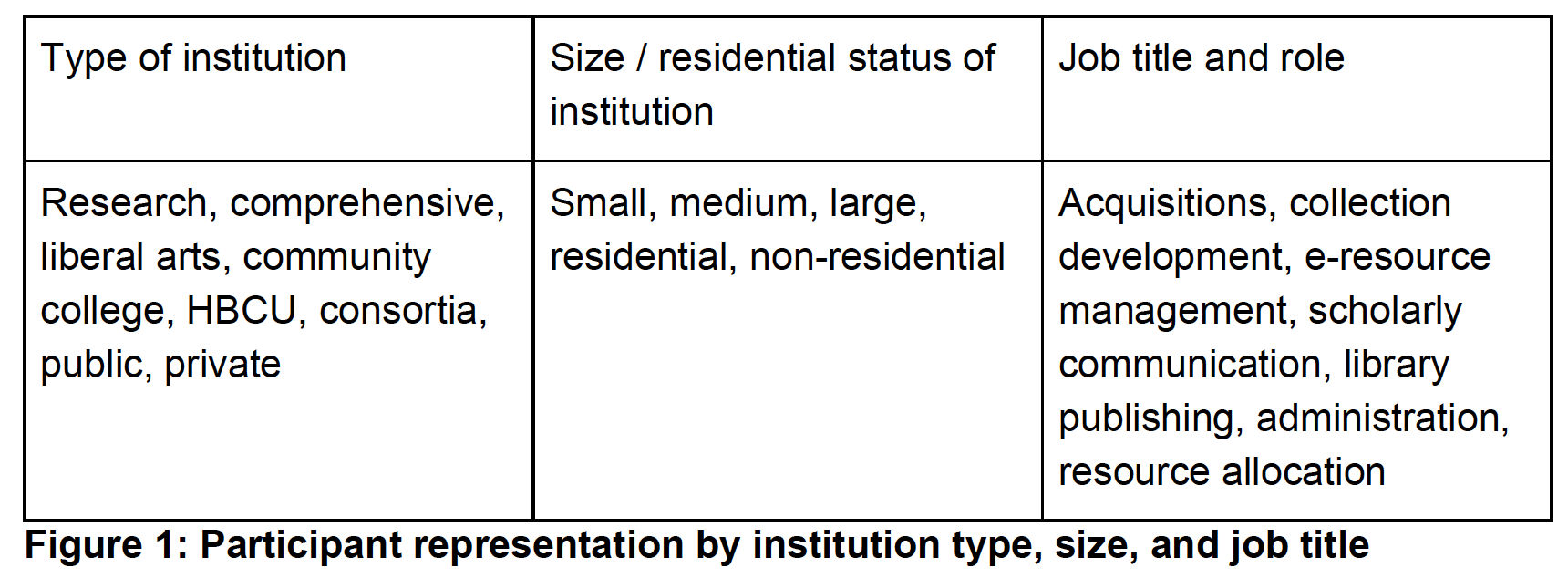

The National Forum project team elected to use a conference-adjacent focus group approach in order to draw from attendance at key professional meetings. IMLS funding enabled the project team to award twelve travel scholarships, two per focus group, in order to reach participants who might not otherwise be able to attend these meetings. We were especially interested in participants who work within collections and acquisitions — including responsibility and participation in consortia entities — as well as those who work within scholarly communication and those who provide service to diverse constituents. Several conferences were considered as potential sites for hosting the focus groups. To provide enough lead time for travel scholarship applications and pre-registration for the focus groups, we focused on conferences held in the spring of 2019. We also wanted to select conferences where we could expect diverse representation of job roles, to ensure that we could populate the focus groups with individuals with varying professional and decision-making perspectives. We settled on three 2019 conferences: American Library Association Midwinter (ALA MW), Electronic Resources & Libraries (ER&L), and the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL). Two sessions were held at each conference, each lasting 90 minutes and consisting of 8-12 participants.

The focus group design process included developing a travel scholarship to encourage diverse representation. Recognizing that a lack of institutional support to attend professional conferences often reduces diversity, we adopted the Digital Library Federation and the Association of Research Libraries (DLF & ARL) travel scholarship model. The scholarship application criteria included identifying as a member of an underrepresented group among library practitioners or working at institutions unable to financially support conference travel attendance. Including the twelve travel scholarship awardees, 58 focus group participants contributed to the dialogue.

Conducting the meetings over three conferences allowed for the opportunity to iterate the structure somewhat, revealing new directions that the project team did not initially anticipate. The tone of the sessions was conversational, providing space for participants to share openly with one another, allowing a natural development of ideas and discussion, while still keeping to the overall question structure.

The focus group questions were developed in concert with Raym Crow of Chain Bridge Group, an expert in the publishing domain. Not all questions were asked at each conference, due to the available time or whether a topic had been sufficiently addressed in a previous question. Appendix A provides the iteration of questions that was used based on what we had learned from the first round of focus groups held at ALA MW. Some questions are grayed out to indicate that these could be skipped if we were running short on time, and some are struck-through to indicate that they did not perform as expected — usually because they were answered through previous questions. At the beginning of each focus group, the facilitator introduced the institutional review board (IRB) informed consent form and audio/video tape addendum consent form and addressed any questions (IRB protocol 19-0018).

At the conclusion of the Forum meetings, the data gathered by the facilitators was shared with Rebecca Kennison of K|N Consultants, who transcribed, coded, analyzed, and compiled the findings. The transcripts were redacted to remove any references to information that might identify the individual speaking, such as the name or type of institution or organization or the geographical location where they worked, specifics about organizational approaches or names of specific teams that might lead to identification of the speaker, references to other institutions that might indicate who else was in the room, and so on. These redacted transcripts are available at https://osf.io/r3jpm/. The original unredacted transcripts were used for the data analysis, which was done using MAXQDA, and consequently are not included in the public folders. A compilation of the results of the answers to each of the individual questions is included, however, and can be found at https://osf.io/yf87b/.

FINDINGS AND TAKEAWAYS

While each focus group developed its own unique conversation, there were several themes that emerged across all groups.

Content vs. Infrastructure and Content Creation vs. Content Consumption

Many participants pointed out that it is almost impossible to separate discussions of collective funding of content and collective funding of infrastructure, or to differentiate between providers of content and the platforms on which that content is hosted. In the focus group discussions, platforms and projects were often mentioned alongside publishers, providers, and organizations. When asked to provide examples of open resources being supported by any given institution, support for infrastructure (e.g., OJS, bepress, Samvera, Pressbooks) was listed almost as often as were OA content providers and publishers. Similarly, paying for OA content creation (e.g., open educational resources [OER], article-processing charges [APCs], and book publishing charges [BPCs]) was often conflated with supporting OA content consumption (e.g., arXiv, Knowledge Unlatched collections, Open Library of the Humanities), although the former was most often seen as a local activity and the latter as part of collective action.

More particularly, participants noted that one of the challenges of open content funding was confusion about what was being supported. Content creation and funding to support that work (e.g., OER, APCs) were considered “resource-dependent” activities that could more easily be invoiced and paid. Supporting mechanisms for content consumption, however, was often more difficult to justify, because the content is freely accessible by everyone globally.

OA as a “Nice-to-Have” Add-On

While philosophical support for OA was strong among focus group participants, in practice OA content was considered by almost everyone as a supplemental “nice to have” rather than as core to the collection. Unsurprisingly, then, OA content funding is often precarious, whether as a small percentage of the overall materials budget or through one-time end-of-year funds or administrative discretionary funds. Support for such content is therefore often the first to be sacrificed during budget cuts. This is especially the case for content considered to be funded collectively rather than locally, with an implicit hope that, should cash-constrained libraries stop paying for such content, the wealthier universities would still provide enough of a safety net to keep the content provider in business.

Who Decides?

One of the greatest challenges to developing collective funding models is that there are widely divergent approaches to decision-making and to funding workflows. The decision-making process might be as simple as one person with funding authority, perhaps including informal consultation, or as complex as multiple committees that may also involve faculty and administrators. Decisions might be made in one day or over several years and may involve offices outside the library.

Although vetting for quality is considered of paramount importance when it comes to open content, there is less clarity around what the vetting instrument should be or what the best mechanism is for indicating quality. Owing to both the wide range of decision-making workflows and the importance of quality, there emerged from focus group discussions the strong desire for the development of clear criteria and perhaps even a centralized clearinghouse or catalog of vetted projects, products, and platforms that could be used to aid decision-making and to speed the approval process. Consortia were seen as obvious and desirable agents to undertake this work, although challenges exist — as will be discussed.

Shared Challenges

Collective funding challenges are shared across a variety of institutions. Whether an Ivy League or large public land-grant university, a small liberal arts college, or a community college, libraries face similar challenges in terms of making locally compelling arguments for supporting collective funding for open content. For example, the local benefit is clear when paywalled content is purchased and limited to those who have been granted explicit access, but the argument tends to default to more generic reasons such as the “public good” or the “land-grant mission” or “student success” when open resources are being supported. In terms of opportunities, one particular type of open content — OER, especially textbooks — has widespread support across all institutional types and sizes, and successful adoption of OER could be leveraged as an entrée into developing support for other types of open content.

Another shared concern, regardless of the size, type, or geographical location of the institution, was the need for transformation of the current tenure, review, and promotion system. The biggest barrier to the success of widespread production and adoption of open content is that the current incentive and power structures do not reward or recognize the importance of OA. “Open” (in all its forms) is seen by many faculty at all institutional types as a utopian vision, rather than a core value, often due to disciplinary pressures to publish in particular journals to achieve promotion and tenure. Consequently, many faculty find themselves unable to engage in this area while still advancing their careers. Faculty are critical partners if we mean to change the scholarly communication dynamics, but this transformation requires a shift in academic cultural practices. Some participants noted that efforts to focus on a single discipline to achieve change seemed to be a promising engagement strategy, especially when librarians who are engaged as fellow scholars were involved, working through and with the disciplinary societies of which they are also members.

Finally, the entirety of the open content landscape is considered by many librarians to be too confusing, with too many projects (some of which are very similar to each other) and too many different models and no clear way to determine worthy projects or initiatives. Librarians at large universities, even those with dedicated scholarly communication librarians, were as likely to cite being overwhelmed and under-informed as were those from smaller institutions.

Summary of Focus Group Discussion

A de-identified list of themed responses can be found at https://osf.io/yf87b/. Due to time restraints and iterative design, not all questions were asked or explored in the same way at each focus group.

Q1: What collective models in support of open resources have your institutions participated in?

Support of open resources covered a wide range of types and projects. (For the full list of projects or organizations mentioned by name, please see the focus group compiled summary, found at https://osf.io/yf87b/.) Most often “support” was taken by the participants to mean monetary payments of some kind, although the question itself did not specify what kind of contributions were being made. As notable as the list of what was mentioned by participants in terms of what open resources were supported was what was not. The Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), for example, was not mentioned by a single participant, although many of the institutions represented in the focus groups contribute to DPLA. Similarly, although collective cataloging projects were mentioned, SHARE was not.

Support of open resources generally fell into these categories:

- Financial support of open-access providers and publishers such as arXiv, Knowledge Unlatched, Lever Press, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), Open Library of the Humanities, PeerJ, PhilPapers, and Reveal Digital; and of infrastructure projects and platforms such as those developed by ArchivesSpace, bepress, Collaborative Knowledge Foundation, DSpace, DuraCloud, Fedora, Open Journal Systems, PubPub, and Samvera.

- Ongoing funding to support article- or book-processing charges (including memberships with publishers such as BioMed Central and publishing projects such TOME (Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem) and the University of California Press’ Luminos).

- Negotiating read-and-publish deals or participation in other offsetting arrangements (e.g., Royal Society of Chemistry’s short-lived voucher program).

- Organizational memberships in groups such as the Coalition of Open Access Policy Institutions (COAPI), Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), HathiTrust, Library Publishing Coalition, ORCID, SCOSS, SCOAP3, and SPARC.

- Cooperative collective development projects such as Dataverse, the now-defunct Digital Preservation Network, GALILEO Knowledge Repository, the California Digital Library, and the Texas Digital Library.

Q2: If you think back to your decision process for supporting an open resource — be it a collection or a platform — what motivated your institution to contribute or what discouraged your institution from participating or contributing?

The main motivations for contribution were either philosophical or practical.

Philosophical motivations included:

- support of the institution’s mission and its strategic priorities;

- enhancement of the institutional brand, particularly being seen as competitive with or a leader among peer institutions;

- commitment to social justice, values-based thinking, and openness; and

- the importance of being seen as contributing to the conversation and the community, even if the part that can be played is a small one.

Practical motivations included:

- being able to show a clear return on investment and to provide indicators of student success and faculty impact;

- the importance of the availability and less restrictive use and reuse of resources both for faculty and students, particularly in support of lifelong learning;

- consortial commitments, especially in reallocation of funds away from commercial publishers;

- requests by faculty or departments to support a particular project; and

- responding to institutional, local, and state politics, particularly when it comes to OER.

Reasons given for not contributing to an open resource were highly practical and almost invariably had to do with:

- a lack of available funds amid a plethora of new initiatives and products;

- the complexity of the funding or access model or the decision-making and/or payment process;

- concerns about lack of governance, transparency, or long-term sustainability and viability of the OA provider;

- lack of support for, or resistance to, OA by faculty, administration, and/or librarians; and

- local restrictions on supporting for-profit entities or state restrictions on public institutions that require state money be spent on a tangible product or service. It is widely understood that the latter can be circumvented by language that talks about memberships or access rather than contributions or donations.

Q3: What local benefit, if any, did your institution receive for supporting a collective initiative?

Participants recognized that OA meant:

- greater impact for individual researchers and scholars, resulting in wider visibility, broader reach, and richer networks, which was seen to be especially important for those faculty at smaller or less-prestigious colleges or universities; and

- a commitment to local engagement, particularly the opportunities to educate and partner with faculty and administrators, to enact culture change both within the library and across campus, and to demonstrate a clear public good to the broader local community.

For those institutions that required a clear return on investment, having an APC or BPC fund or participating in some way in offsetting OA costs was the clearest local benefit.

Local benefit tended to shift depending on the size and type of institution. Foremost among the larger, research-intensive universities and their libraries was branding, whether that was described as visibility, impact, reputation, or name recognition. Branding also included locally produced publications or data in the institutional repository, as well as the publicity that came from winning grants or supporting projects. For smaller or teaching-intensive colleges, cost savings to students was considered most important.

Several participants noted that changes in institutional administration or library leadership can directly affect priorities or budgets and be the death-knell of OA projects that are not funded by their own endowment. Participants expressed grave concerns about the possibility that support for valuable content might cease due to personnel changes.

Q4: What restrictions are in place for how money is being spent on open resources? What kinds of policies, if they exist, does your institution have regarding providing financial support to open resources? How closely or consistently are they followed?

The most common restrictions have to do with terminology and designated funds. Many participants noted that they are not allowed to “donate” but must instead become “members” or be seen as “acquiring a collection”; this is especially a problem for public institutions. In addition to the requirement for state institutions to purchase a tangible product or service, some states also will not allow funds to be used for something that will benefit others outside the state, which is a particular conundrum for open content.

Q5: We’ve talked a lot about motivations to support open resources. Which one would be the most important to your institution?

Answers to this question generally fell into three categories: impact, mission alignment and community engagement, and cost savings.

IMPACT. Increasing impact and thereby enhancing the reputation of the institution was considered by many participants to be the main driver for decisions to fund open resources. Impact — whether local, global, or social — was variously described in terms of:

- improved analytics;

- greater access to collections and increased use of those collections;

- increased institutional reputation (what one participant called “institutional self-interest”);

- clear value propositions (e.g., showcasing the work of faculty and students, showing the importance of libraries); and

- the importance of contributing to the sustainability of a promising project or initiative (e.g., will it last long enough to be transformational?).

Several participants observed that they found it compelling to support, even if in small or incremental ways, the transformative work that has been done, particularly by library leaders such as MIT and the University of California system.

MISSION ALIGNMENT AND COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT. These concerns closely followed impact as a cited motivation for contributing to open resources. This was especially the case when the service was direct and local (e.g., contributing to student success in terms of retention, progress, graduation) and when the perspective was from a Community college or a land-grant institution. Sometimes such alignment was couched in terms of principles and core values, such as a “philosophy of open” (including open pedagogy). Some participants noted that what really influenced the decision was the preparedness, willingness, or consensus of library staff (or faculty) to support an initiative, emphasizing the importance in and of itself of the opportunities OA provides for outreach, education, and advocacy both inside and outside the library.

COST SAVINGS. Financial incentives that factored into decisions to support — or not support — open resources included a clear cost reduction, elimination of financial barriers (especially when the savings can be passed along to students), and requirements placed on additional library resources.

Q6: What is the decision-making process for supporting open collections and open resources at your institution and who is involved in that? How might open resource spending requests be presented to simplify their review and approval at your library?

An umbrella caveat to this question was that the decision-making process can vary depending on where the money is coming from, whether the resource is a renewal or not, and/or whether administration was approached first. One focus group succinctly summarized this as “it depends.” The complexity of the decision-making process was also directly related to the size of the institution. The smaller the school, the more likely it was that a decision to support a resource would be made by a single individual, such as the collections officer, albeit often in informal consultation with other colleagues or administrators. The larger the institution, the more likely it was that decision-making involved one or more committees that do an investigation and make a recommendation to an executive team or administrator for approval.

The basic decision-making workflows could be summarized this way:

TOP-DOWN. Decisions to support a project or initiative might come directly from library leadership (e.g., dean/director/university librarian or executive team), even if some other process is also in place. Decisions may also come from university/college administration (e.g., president, provost, research office, deans), especially when they are providing funds for initiatives they want to support. Other powerful stakeholders who might provide input include faculty, departments, or students. These stakeholders make requests that are then reviewed by library staff or committees or that follow some other established workflow. A small number of participants observed that external forces (e.g., federal or other funder mandates) greatly influenced collective support considerations.

COLLECTIVE. Quite a few decision-making workflows involved groups of people, such as deans collectively (e.g., deans’ council at the university level or all library deans at public institutions at the state level) or consortia (e.g., in terms of what already-indexed OA content gets turned on). More often, however, are collective library-guided decisions made formally by a committee or sometimes several committees with approval or guidance from senior leadership. These may be faculty-led committees that include librarians or library-only committees, sometimes following established policies, guidelines, rubrics, and checklists and sometimes not. This approach is the one generally taken by large libraries, whether research-intensive or not. Smaller libraries often involved the entire library staff, either using consensus or majority vote to make a decision. Libraries of all types and sizes may utilize informal small groups (e.g., the scholarly communication librarians, subject liaisons, and collections librarians together), and may follow established policies, guidelines, rubrics, and checklists before making recommendations.

INDIVIDUAL. In addition to an individual administrator (e.g., provost, library dean) who might make a request, several participants reported a mostly autonomous process, even if a decision needed to be approved by upper administration. In one example, an individual librarian presents a recommendation to their director, who goes to the provost, who then gets ultimate approval from the president. Other individuals who might have the authority to decide to support an open resource, such as collections officers or collections strategists or subject liaisons, often will also have conversations with the library dean/director or collect input from faculty even if the ultimate decision is theirs.

Q7: What do you think should be avoided (or adopted) by OA providers when presenting collective offers?

The answers to this question provide a list of useful tips for any OA provider who wants to secure collective funding. Some of the advice focused on the importance of excellent customer service, such as good communication, willingness to answer hard questions as part of due diligence, patience and understanding with the sometimes complicated decision-making process, and easy-to-understand invoices. Several participants offered variations on this umbrella advice: Think like us, share our values, and (as much as possible) be like us (e.g., non-profit). The rest of the advice fell into two categories: transparency and strategy.

TRANSPARENCY. Participants urged OA providers to be as transparent as possible about the organization and its business: its mission, values, goals, value proposition and benefits, governance, sustainability plan (especially if currently grant-funded), and preservation and perpetual access plans. Such transparency includes explaining how pricing decisions are made, why the organization has chosen to be non-profit or for-profit, how funds will be used, and how this product differentiates itself from a similar one and why libraries should support both. Several participants urged OA providers to avoid developing complicated access models (e.g., tiered access based on level of contribution) that might be seen as reinforcing inequities among institutional types or geographical locations.

STRATEGY. OA providers were urged to be familiar with state restrictions regarding funding organizations and requirements that requests be phrased in a very specific way (e.g., avoid words like “donate”). Participants expressed frustration with OA providers who did not do their homework on the institution or about state regulations, resulting in a waste of everyone’s time. OA providers were urged to work with and support advocacy organizations (e.g., SPARC) that are already pushing others (e.g., legislatures, funders, foundations) to provide funding (carrots) or create mandates (sticks) to ensure there is greater awareness of OA, thereby making it potentially easier for libraries to fund open content.

The focus groups did surface two pieces of advice on strategy that might seem at odds with one another. Some participants advised that OA providers establish themselves first with more risk-taking institutions and develop a track record before coming to more risk-averse or conservative institutions. Others argued that OA providers should not always start with the “usual suspects” (i.e., ARLs and R1s, who may be more risk-taking), but instead develop business models that are designed to allow smaller institutions to participate from the start. Participants urged these providers to intentionally leverage consortia that include smaller institutions as they are developing their market strategy.

Q8/Q9: What role, if any, do you think consortia might play in accelerating or simplifying your participation in supporting open resource initiatives? All things being equal, would you prefer to channel your participation through a consortium?

There was general enthusiasm for the role consortia might play, with one participant observing that engaging consortia in this work seems the next logical step in academic libraries’ evolution. What once were isolated conversations about OA among scholarly communication librarians have now become discussions throughout the library and across the institution. It now makes sense, this participant observed, to broaden the participation further by engaging in consortial conversations. Several participants noted that to be maximally successful consortia needed to act nationally, not merely at the local, state, or regional level. They argued for either a consortium of consortia (such as International Coalition of Library Consortia) or a nationwide non-profit such as LYRASIS or SPARC taking on such work. An unanswered question is how libraries who are not members of consortia would be affected or included.

As in the advice to OA providers, there was a specific list provided by participants of what consortia might do to expand on the roles they already play in advocacy, business and community development, collective action, and analysis.

ADVOCACY. Consortia were seen as able to use their visibility and credibility as collectives with decision-making authority to undertake a number of initiatives on behalf of their members, particularly if they coordinate their efforts. These activities included collecting community expectations and needs and sharing those with communities of interest, advocating at a higher level (e.g., state legislatures, Board of Regents) for initiatives that the consortium as a whole or a collection of consortia wants to support, and leveraging the differing membership types (e.g., some consortia have library members, some are made up of provosts/deans, some have both) to get maximum benefit. However, some libraries belong to several consortia, and it was not clear how advocacy could be coordinated in a multi-consortia environment. Several participants noted that of necessity these different types of consortia need to be engaged — library consortia for licensing, university administrative consortia for advocacy — but that the combination could be powerful.

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT. Participants saw an important role for existing consortia, as respected and established entities, to bring together both larger and smaller institutions in the collective decision-making process as to what products, platforms, and initiatives to support and in giving a voice to institutions of all sizes and types. Consortia were seen as a way for larger, well-funded universities to support the work done by and at smaller colleges and universities and vice versa. Nonetheless, there is some concern that those with the deepest pockets have the most influence in the work of the consortium. Consortia were lauded for their ability to convene wider community conversations that enable both formal and informal networking and knowledge-sharing so that everyone can learn from each other and take new ideas back to their local communities. Several noted that consortia provide built-in networking, making it easy to reach out to counterparts at other institutions to ask what they are doing and where they have succeeded or failed.

BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT. Consortia were also envisioned as playing an active role in helping OA providers by assisting new providers with their marketing, business planning, and infrastructure to successfully launch a product. Consortia may also assist existing providers by being the conduit for product requests from their members, rather than each institution requesting improvements on its own. A more radical proposal was that a consortium or consortia working together might take on the challenge of developing an OA funding model that eliminates APCs.

COLLECTIVE ACTION. Consortia are often designed specifically to enable collective bargaining and brokering, thereby mitigating risk for individual members and providing additional credibility, as consortial decisions can carry more weight than individual ones. Participants could therefore extend their current portfolio to include open content. Examples of work consortia might undertake include brokering OA publish-and-read or read-and-publish deals as part of consortial subscription negotiations, as some state consortia have recently done (OhioLINK 2019; VIVA n.d.), thereby leveraging economies of scale that might include bulk discounts for offsetting agreements, or paying OA providers via the consortium membership dues. A potential limiting factor, however, is that consortia are often slow to act in some areas precisely because they are acting in a collective manner, with diverse stakeholders. This rate-limiting approach can create tension among institutions that wish to move quickly and assume more risk.

ANALYSIS. Many participants, particularly those from smaller or less well-resourced institutions, felt a major role consortia could play was in undertaking research, analysis, and vetting activities on behalf of the membership. Ideas varied widely, including tracking new initiatives and doing the research to understand and evaluate the model(s), clearly explaining them to membership; acting as a clearinghouse that provides a list of vetted initiatives to choose from (including homegrown solutions); and potentially managing collective funding of those initiatives on behalf of members by providing regular analysis (e.g., statistical reports).

Q10: Do you have any thoughts that haven’t been voiced yet with respect to collective action or collective funding of open collection development activities?

As might be expected from the breadth of the question, there was a wide range of responses. Some of these delved into the critical nature of how we assess quality and whether there is uneven scrutiny applied to open content support compared to subscription purchase decisions. Some responses focused on technical concerns, such as how accessibility is provided or the compatibility of open content with existing discovery systems. It was clear in several focus groups that existing systems do not accommodate open content well, raising the concern that addressing OA content development must consider discoverability and access simultaneously. Finally, several focus groups discussed the importance of faculty as agents for changing the promotion, review, and tenure expectations to include or even privilege OA.

CHALLENGES

Arising from the focus group discussions were a number of challenges that have traditionally stymied collective funding efforts for open content.

What exactly are we funding?

As noted earlier in this paper, several projects are focused on funding infrastructure rather than content. This project sought to narrowly address open content and not infrastructure. What we have learned in our discussions, however, is that it is difficult to decouple content from infrastructure and that many of the same concerns that are raised about supporting open infrastructure are also raised about open content.

How, for example, should sustainability be defined? Sustainability was invoked frequently throughout our focus groups, but there did not seem to be great clarity on what criteria should be applied to be able to say with certainty that a project, product, or initiative is or could be sustainable. Is sustainability a question of preservation, maintenance, community-building, financial security, or all of these? How would an OA publisher or platform achieve an “A” rating in an environment where open is considered “nice-to-have” rather than a crucial expenditure and thus on unstable financial footing?

Some comments from participants seemed to question the idea that grant-funded projects might envision their sustainability plan as involving library funding once the grant ran out. If these initiatives should not turn to libraries for sustainable funding, to whom should they turn? Adding to the sustainability question is the effort involved in having to re-evaluate funding projects that shift their sustainability strategy midstream, like the Knowledge Unlatched tax status change from not-for-profit to for-profit and the acquisition of independent entities Mendeley, SSRN, and bepress by the publicly traded commercial firm Elsevier.

Why is supporting open so complicated?

The paywall system is relatively easy. Want to gain access to a subscription/book/database? Write a check. Models to fund open content are much more complicated because, unlike in the paywalled system, there are very few OA providers that provide an incentive to pay once the content is made openly available. There is also little shared understanding of what we have called the “free-riding threshold” (Marks, Lehr, and Brastow 2006). At what point does the financial support for an OA content provider diminish to the extent that an OA project becomes financially unsustainable? In the complicated OA business model, “free-riders” have an impact on OA content providers. To envision the problem, how long would a subway system remain running that allows anyone who wishes to pay to ride to do so, but charges no one at the gate? Those who believe in public transportation as a public good would pay to keep the system running. But would they be willing to pay for 100 or even 1,000 others who also ride the train but who are happy to have someone else pay for their ride or who cannot afford to pay? To combat this problem, many OA projects and providers have, it seems, taken a number of different approaches to financial sustainability, which has in turn created confusion and consternation. Business models are often complicated, and the sheer number of individual OA projects, platforms, and initiatives is overwhelming and requires additional resources outside of the traditional acquisitions and collections workflow.

While there is an understandable desire to move away from the APC/BPC model of funding open content (Green 2019), that model is the most familiar and introduces little change to the traditional system: if someone does not pay upfront, the content will not be released. Because such payment-for-publication models work as incentives to pay the invoices and are fairly easy to process as a transaction, these models have been more broadly adopted. Despite focus group participants often pointing to APCs as a way to support OA, the APC/BPC model can nevertheless be seen as a deterrent to collective action because of its association with individual, local benefit and owing to the inability for all institutions to fund at the same level.

In addition, open content is as expensive to produce as closed content. In an all-open world, the real savings occur at the backend, by eliminating the mechanisms, workflows, and processes that are required to prevent access. Open content requires the same efforts to enable discoverability and reusability as closed content, such as the labor required to create metadata and XML, as well as some additional downstream complications, such as the labor required to normalize metadata that may be supplied insufficiently by content producers who do not follow best practices or standards. All of these concerns are exacerbated by the widely variant expenses associated with producing short-form versus long-form work — or with unique formats such as digital humanities projects or datasets. Publishers have long known how to provide cost-per-piece pricing and how to collect that amount. In a world where cost-per-piece pricing is obsolete, what mechanisms can be put in place to provide transparent cost explanations, so there can be clarity when libraries are faced with wildly divergent costs propositions from providers?

How do I know what to support? What if I’m the only one?

Two final but related challenges stand as roadblocks to successful collective funding efforts for open content.

The first is that no one person can know everything that is happening in this space — which means everyone needs to contribute to that effort. Before there can be collective funding, there needs to be collective information-sharing. Efforts to do so must not be labors of love by passionate volunteers, but designated responsibilities of resourced staff. Such efforts take considerable time, effort, and communication. For example, those who took part in the “Mapping the Scholarly Communication Landscape 2019 Census” — a one-time event — found it challenging even within their own organizations to gather the information needed to respond to the Census questions (Skinner 2019). Imagine needing to do that work constantly to stay on top of what is happening locally, regionally, nationally, and internationally to make an informed decision as to what projects, platforms, and initiatives are available for support and how to participate. Similar expertise challenges exist for OA providers, whether they are launching new projects or maintaining established ones. Many paywalled content providers and aggregators have developed robust sales and marketing staff whose sole job is to facilitate sales and client relations. OA projects are often academic-led endeavors facilitated by scholars and researchers who wear many other hats and have competing priorities.

Second, the challenge of the “collective good problem” outlined above remains. Even if an institution has done the research and reached the decision that a project, platform, or initiative is worthy of support, how do we overcome the problem that a single institution alone cannot support this entity? How do we find like-minded institutions who will commit to long-term sustainability? What can we promise today to those OA providers? Will the same be true tomorrow or next year or five years from now? Consortia navigate a similar problem, due to the complexities of their membership, which can make it difficult to take risks or to move quickly.

OPPORTUNITIES

For all the challenges we heard to collective funding efforts during our discussions, we also unearthed several opportunities. As is perhaps appropriate for a series of focus groups on collective funding, the various heterogeneous configurations resulted in some collective wisdom and considerable cohesion around opportunities for libraries and library consortia to play a proactive role in transforming the current environment.

Rethink collection development.

A crucial first step in embracing the opportunities available to libraries to further an open world is to consider OA content as core to collection development — on a par with, if not perhaps superior to, paywalled content. What we heard in our focus groups is that most OA content is seen as “nice to have” rather than as a critical component of the collection. There were perspectives that OA content is only applicable to research-intensive universities; or that it is niche, at too high a level for undergraduates, or not focused on practical or technical skills. Essentially, open content falls outside the scope of collections policies. This perception may be one reason that when money is tight, support for OA resources is readily discontinued. But is it the reality? The nascent movement to create criteria for determining the quality of an open resource (discussed further below) may begin to uncover and make discoverable content that is broadly appealing, pitched at the appropriate level, practical, and valuable.

Rethinking collection development to put open content at the heart of an institutional policy breaks down the isolation of current collection practices. Traditionally, collective collection development most often happens at the local or regional level. What does collection development look like when quality content can be produced by any scholar who leverages the Internet, rather than only those who use traditional mechanisms and conduits of publication? How can and should this globally available content be curated for local consumption? In this area more than any other, there are many kinds of collective contributions that go beyond funding, including efforts to improve discoverability or to highlight content that has resonance with local priorities (e.g., tagging content appropriate for community college students or highlighting the work for local faculty). With this expansive approach to collective collection development, there can be a place for everyone to contribute. Perhaps even more importantly within the library community, rethinking collection development to put open content at its heart bridges the divide that often exists between acquisitions and scholarly communication cultures, both within and across institutions, creating teams of experts where before there were silos.

Develop community-informed requirements for evaluating OA content.

For a rethinking of collection development to be successful, we need to develop new ways of thinking about criteria, rather than relying on or defaulting to traditional collections criteria. The library community has collections criteria for closed content, through collection development policies and local needs considerations. That criteria might include input from the providers (a database vendor or a scholarly publisher) and input from the campus community (a faculty member, accreditor, or administrator). Working together with scholars, students, and the broader OA community, libraries have an opportunity to apply our expertise to collectively design and participate in vetting mechanisms for OA resources. What criteria might exist currently but would need to be rethought entirely for open content, such as those for funding or pricing, content quality, metadata and discoverability, integration, or preservation? What criteria (if any) would be completely unique to open content? And at what level should these criteria be set — locally, regionally, consortially, nationally, internationally?

Such a heady opportunity requires collective activity, especially to address the challenge raised about shared communication across the rapidly shifting OA landscape. This approach provides an exciting opportunity for collective community action and addresses a recurrent need expressed across the focus groups.

Create new staffing and resourcing models as we shift to more open content.

At the heart of a community-driven collection development approach is a requirement that traditional library workflows undergo change. We must recognize that the staffing designed to support workflows in a closed (and enclosed) environment are not the ideal workflows and staffing to support open content production and collection, considering the local effort required to support open infrastructure and open content discoverability within systems. Undertaking this transition will require a care-based approach to professional development while inculcating within the organization the importance of everyone’s participation in this transition (The Information Maintainers 2019). Determining the ideal staffing and workflow models — as there should be some variation across different types of institutions — will be a significant undertaking for the profession, but with the potential for transformative change.

CONCLUSION AND NEXT STEPS

In “The 2.5% Commitment,” David Lewis (2017) suggests that the commitment to open infrastructure will only happen if it becomes both normative and institutionalized — through library membership organizations, academic institutions, or accrediting bodies. Our series of focus groups, focusing on open content, explored how individual library decision-makers and influencers might behave in such a normative, institutionalized environment. What information, commitments, and coordination would they need from providers and peers to participate in supporting OA content providers? We hope that the findings, challenges, and opportunities identified in this paper elucidate some of that landscape. One of our goals for this project was to motivate participants to keep engaged with the topic after the focus group session. We were encouraged to see informal community-building begin among participants at several of the focus groups. After the official end of several of the sessions, participants discussed with one another their processes, criteria, and funding, as well as hurdles and goals. Several participants exchanged information with one another and were excited to continue the conversation beyond the conferences.

As noted in the introduction, this project has taken place at a time when many different groups have taken up the question of collective action and support for open content, infrastructure, and practices. The University of Arizona Libraries (n.d.) announced that it was transitioning its Open Access Publishing Fund to an Open Access Investment Fund, and the University of Guelph (n.d.) has made open initiatives part of its strategic plan. There are signs that other academic libraries (University of Minnesota Libraries, n.d.; Wilson et al. 2019) are considering similar directions. Continued research in collective action through consortia (O’Gara and Osterman 2016), the models used for scholarly communication (Hartley et al. 2019), disrupting market philosophies (Ghamandi 2018), and lessons learned from previous collective action efforts (Schonfeld 2018) demonstrate how dynamic, interconnected, and current this work is. As these and other global coalitions and projects continue to emerge, addressing recommendations and funding structures, we hope the insights of our participants will inform their work.

In her book Generous Thinking (2019), Kathleen Fitzpatrick acknowledges that competition permeates higher education, for both faculty (recruitment and promotion) and institutions (prestige). Yet arguments exist for colleges and universities to build public engagement, and OA research and scholarship are foundational to demonstrating public good as an

institutional value. Following Fitzpatrick, we believe have reached a point in the OA ecosystem where competition is a detriment to collective action and the public good, and the Mind the Gap team has succinctly explained how competition for one-time grant funding has created an OA landscape of dynamic diversity at the expense of sustainability at scale (Maxwell et al. 2019). We envision future research in the area of OA content and

infrastructure to examine and build on the dialogue and critique of recent studies, taking the next step toward sustainable and, to a certain extent, standardized collective initiatives. Developing a common vocabulary with one another is one step toward developing a common understanding and undertaking common work.

Further Research

Using what we heard in the focus groups and synthesizing that with current research in the field, we offer the following project ideas to the community, as potential next steps to actualize collective OA collection development and support:

- Distribute a survey to library workers to elicit criteria for OA content selection, including quality measures and financial workflow components.

- Research appropriate levels of collective action — local, state, regional, national, international? What is the tipping point between large enough to exert market force and too large to manage? What is the role of consortia in leading collective action efforts?

- Propose and test innovative staffing and workflow changes to meet the needs of an open environment.

- Research the power and agency of the library community with respect to OA content support:

- Would community criteria, decision-making, or vetting be widely adopted?

- How is best to consider needs in relation to the diversity of institutional participants and scale of effort?

- How can the community leverage market power in an equitable and ethical way?

- Create generous spaces and build a common vocabulary, within the library profession and with content providers.

- Expand conversations about these topics to include other stakeholders (OA providers, consortia, agencies, societies, faculty and scholars, administrators, etc.).

- Explore the connection between OER and OA programs. Are there ways to use the momentum from OER programs to develop stronger OA content platforms or services?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research team would like to thank the focus group participants for contributing their expertise, interest, and time to this project. We would also like to thank the conference organizers of ALA Midwinter, ER&L, and ACRL for providing logistical support and space for the focus groups.

REFERENCES

Dowding, Keith. 2013. “The collective action problem.” Encyclopedia Britannica.

Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. 2019. Generous Thinking. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ghamandi, David. S. 2018. “Liberation through cooperation: How library publishing can save scholarly journals from neoliberalism.” Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication 6 (2): eP2223.

Green, Toby. 2019. “Is open access affordable? Why current models do not work and why we need internet-era transformation of scholarly communications.” Learned Publishing 32: 13-25.

Hartley, John, Jason Potts, Lucy Montgomery, Ellie Rennie, and Cameron Neylon. 2019. “Do we need to move from communication technology to user community? A new economic model of the journal as a club.” Learned Publishing 32: 27-35.

The Information Maintainers [Devon Olson, Mark A. Parsons, Juliana Castro, Monique Lassere, Dawn J. Wright, et al.]. 2019. Information Maintenance as a Practice of Care.

Lewis, David W. 2017. The 2.5% Commitment.

Marks, Melanie, David Lehr, and Ray Brastow. 2006. “Cooperation versus free riding in a threshold public goods classroom experiment.” The Journal of Economic Education 37, no. 2: 156-70.

Maxwell, John, Erik Hanson , Leena Desai, Carmen Tiampo, Kim O’Donnell, Avvai Ketheeswaran, Melody Sun, Emma Walter, and Ellen Michelle. 2019. “Prospects.” In Mind the Gap: A Landscape Analysis of Open Source Publishing Tools and Platforms (1st ed.).

O’Gara, Genya, and Anne C. Osterman. 2019. “Negotiating on our terms: Harnessing the collective power of the consortium to transform the journal subscription model.” Collection Management 44 (2-4): 176-194.

OhioLINK. 2019. “OhioLINK breaks new ground in open access with Wiley.” Accessed August 26, 2019.

Schonfeld, Roger C. 2018. “Why is the Digital Preservation Network disbanding?” The Scholarly Kitchen (blog), Society for Scholarly Publishing. December 13, 2018.

Shorish, Yasmeen, Raym Crow, Rebecca Kennison, Judy Ruttenberg, and Liz Thompson. 2018. “Supporting OA collections in the open: Community requirements and principles.” Institute for Museum and Library Services National Leadership Grants for Libraries.

Skinner, Katherine. 2019. Mapping the Scholarly Communication Landscape 2019 Census. Atlanta: Educopia Institute.

University of Arizona Libraries. n.d. “Open access investment fund.” Accessed August 21, 2019.

University of Guelph Library. n.d. “Open scholarship support.” Accessed August 21, 2019.

University of MInnesota Libraries. n.d. “Open access publishing fund.” Accessed August 21, 2019.

VIVA. n.d. “VIVA broadens open access for Virginia with a new Wiley agreement.” Accessed August 26, 2019.

Wenzler, John. 2017. “Scholarly communication and the dilemma of collective action: Why academic journals cost too much.” College and Research Libraries 78, no. 2: 183-200.

Wilson, Lizabeth, Denise Pan, Chelle Batchelor, Tania P. Bardyn, Corey Murata, Gordon J. Aamot, and Elizabeth Bedford. 2019. “For the public good: Our values in a changing scholarly communication landscape.” Scholarly Publishing and Open Access (blog), University of Washington Bothell Library. March 12, 2019.

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Focus Group Script

A. As participants walk in

INSTRUCTIONS FOR MODERATOR: Pass out consent form and explain it.

SCRIPT: Before we get started, please read this consent form. The form provides information about what we will be doing today in the discussion group. It also gives you a chance to decide if you are willing to take part in today’s group or not.

[Pass out consent forms. Have participants fill out bottom part of form based on their decision to take part or not. If participants choose not to take part, thank them for coming and have the note taker escort them out.]

A.1 Introduction

INSTRUCTIONS FOR MODERATOR: Allow two minutes for this section.

SCRIPT: Hi, I’m __________ and this is __________. We are from James Madison University. If you have any questions about the consent form or the nature of the study prior to signing, please let the team know, and let us know if you’d like your questions to be answered in private.

Thank you for joining us today.

Our project seeks to explore library attitudes about collective models for channeling financial support to open resources. This exploration includes a series of focus groups, like this one, targeting primarily North American colleges and universities of various types and sizes.

To help design effective approaches to funding open resources, our research seeks to understand what motivates institutions to contribute to the support of open resources — and what may discourage them from doing so. We want to understand the attitudes not only of institutions committed to open access, but also of institutions that might be less actively committed to OA.

We would like to audio record today’s conversation. This will help us ensure we accurately reflect what was said. The recording will be kept on a password protected computer.

Today’s discussion will last about 90 minutes. Everything we talk about will be confidential. This means that we will use general ideas from our conversations in a report but there will not be any names used. You may use names in the discussion today and when they occur they will be de-identified in our transcription. Are there any questions about today?

B. Agreements

INSTRUCTIONS FOR MODERATOR: Allow two minutes for this section.

SCRIPT: Next, we’d like to go over a few agreements that will help guide our conversation.

- Please talk one at a time and speak up as much as much as possible. We encourage you to sit near one another so we can hear what everyone has to say and so the recorder picks up everyone’s voice. This will make it easier for us to hear each other.

- Feel free to respond to each other about these topics, not just answer my questions. This will help us have a good discussion about each topic.

- Please respect one another’s opinions. There will be a range of opinions and experiences on the topics, and we do not expect everyone to agree with each other. If you disagree with what others might say, please feel free to say so (respectfully, of course). All perspectives are valuable for our research.

- We would like to keep today’s discussion confidential. While people may share great ideas in this room, please do not use any names when recounting those ideas without the permission of the individual. Also, please don’t say anything here that you don’t want others to know.

- Because we only have 90 minutes, we may have to shorten parts of the discussion and move on to another question.

B.1 Participant Intros

INSTRUCTIONS FOR MODERATOR: Allow six minutes.

SCRIPT: Let’s find out some more about each other by going around the table and introducing ourselves. Please give your name and role at your institution.

C. Main Questions

INSTRUCTIONS FOR MODERATOR: Start recording. Allow 70 minutes for this section: 40 minutes for motivations, 30 minutes for decision-making. Revisit motivations if necessary and time allows.

Motivations

SCRIPT: We’d like to start by exploring your institution’s motives and objectives for participating — or not participating — in collectively funding open resources.

1. What collective models in support of an open resources have your institutions participated in?

[If necessary, refine the group’s understanding of how you’re defining a collective action (e.g., Knowledge Unlatched, Open Book Publishers, Open Library of the Humanities, etc.) and open resources (e.g., content, OA journals; OSS platforms; registries/directories, DOAJ, Sherpa/RoMEO, etc.).]

2. Thinking back to your decision process for supporting an open resource, what motivated your institution to contribute—or discouraged you from contributing?

3. How important were the decisions (to contribute or not) of other libraries — especially libraries similar to yours — to your decision? Very important, kind of important, not at all important? [Show of hands.]

4. How important was your institution’s reputation — that is, the perception of peer institutions — in your contributing to a resource’s support? Very important, kind of important, not at all important? [Show of hands.]

5. What local benefit, if any, did your institution receive for supporting the collective initiative?

6. How important was the local benefit in your decision to participate? Very important, kind of important, not at all important?

[Given the prevalence of governance input as a benefit, it would be useful to probe as to the importance of this benefit across initiatives. For example, is governance input more important for some types of initiatives than for others? And, if so in what cases and why?]

7. What restrictions are in place for how money is spent on open resources? [What kinds of policies, if any, does your institution have regarding providing financial support for open resources? How closely or consistently are they followed?]

Closing questions:

- Of all the motivations to support open resources that we’ve discussed, which one is most important to your institution participating?

- Do you have any other comments on why libraries might contribute, or not, to the financial support of open resources?

Decision-making

SCRIPT: The time and cost required to organize and coordinate collective support for open resources can pose barriers to the success of collective funding efforts. We’d like to explore how your institutions operate and how they might be designed to streamline decision-making.

1. What is the decision-making process for supporting open resources at your institution? Who is involved?

2. Are there simpler ways that the OA providers could request funding? Thinking from the collection development side, how might open resource funding requests be presented to simplify their review and approval at your library?

3. What do you think should be avoided when presenting collective support offers?

[Do you think your institution would be willing to enter a non-binding pledge to contribute to certain types of open resources under certain conditions? (For example, pre-approved support for certain types of resources, pre-approval up to a certain investment level, etc.?) Is such a pledge advantageous?]

4. What role, if any, do you think consortia might play in accelerating or simplifying your participation in supporting open resource initiatives?

5. All things equal, would you prefer to channel your participation through a consortium?

D. Wrap-up

INSTRUCTIONS FOR MODERATOR: Allow ten minutes.

SCRIPT: Our time is almost up. Any other thoughts or comments on how the decisions to support open resources might be improved or simplified?

Thank you so much for sharing your opinions and ideas today.

Appendix B: Related Projects

The OA Switchboard from the Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association

Virtual Library of Virginia (VIVA) consortium’s model for sustainable journal pricing

OCLC’s efforts in providing more visibility to open content

Guiding principles of the Open Textbook Network: the common good, equity, inclusivity, action, humanity, integrity, shared abundance